If you’re lucky enough to be one of the 20% of projects that fund within the first 10 days, you might be wondering “what next?”

For product-based projects, you may find you continue to sell more and more of your product. But your new problem (and it’s a good problem to have) is that economies of scale will begin to kick in and your product will start to cost less to produce.

For arts and events projects, you may find the project hits the wall – now you’re over the line, people don’t see the point in backing you anymore.

So what to do with that extra cash? Or how do you give your project a kick in the pants so your final outcome is even better than the original plan?

The answer, is stretch goals.

What is a stretch goal?

A stretch goal is an additional goal beyond your initial funding goal. For many projects, this is a financial goal, however some (such as the Exploding Kittens project) use it as an opportunity to build their crowd.

In essence, a stretch goal brings you more money, and gives your backers an incentive to help you get there.

What makes a good stretch goal?

A good stretch goal means that your final product will be better for everyone.

When you come up with your initial funding goal, you should be focussed on minimum viable product. That means asking for the lowest possible amount to get the job done to the minimum standard (keep in mind that your ‘minimum standard’ can still be a first-class product).

Stretch goals are about providing the bells and whistles. Extra functionality or a better product.

It should be something that your whole backer community wants to see. If there’s one thing they’re all screaming out for, then it’s worth considering that thing as a stretch goal.

What makes a bad stretch goal?

The biggest mistake I see people making with their stretch goals is making more work for themselves.

Stretch goals should never compromise your initial timeline. You should still be delivering what you promised, as close to the time you’ve promised to deliver it as possible.

Stretch goals should enhance your original idea, not expand it.

For example, if you are making a locally-based documentary, and you promise to get an international perspective on your topic, this is potentially going to make your film longer, will mean travel for you and your crew, and could push out deadlines.

Instead you may want to consider adding a better soundtrack – use the extra funds to license songs, or hire a composer.

If you are making a product, then consider adding extra product to backers over a certain threshhold. Or use better materials for a better quality product. Don’t go making new products or adding considerable new functionality to your original proposition.

How do I ‘do’ stretch goals?

This one’s important. So many people publicise their stretch goals in their original campaign. Here is the problem I see with that.

“Hi, I want $10,000 to make this thing. And when I get that, I’m going to ask you for another $5,000 so I can make that thing slightly better. And once I’ve got that, I’ll ask for another $20,000 to make more of them for everyone!”

The projects I’ve seen do this typically fall into the 80% of successful projects that raise less than 10% over their initial goal. They won’t fund until the final 5 days. There is no time to reach these goals.

Not only that, but you leave yourself open to so many questions and judgements such as:

- Why are you only asking for $10,000 when what you actually need is $35,000?

- They’re so greedy, $10,000 is heaps to get their project done. They can get it from someone else.

- Why can’t you do all those things now?

It pays to think about stretch goals in advance, but for the love of all that is good and holy – don’t talk about them until you’ve actually funded!

Who has done stretch goals well?

Stretch goals can be about money, but my favourite example of stretch goals was about growing the crowd. This was done in early 2015 by The Oatmeal on the Exploding Kittens Kickstarter project. I liked it so much I broke down what they did in detail. You can read that casestudy here.

That said, one of the best examples I’ve seen of stretch goals happened in the Reading Rainbow Kickstarter project. I’d recommend reading through the project updates for a full account of what happened, but an overview:

May 29, 2014: Project launches with $1,000,000 goal. Project funds on Day 1.

May 31, 2014: Project hits 200% of goal and starts talking about stretch goals. Releases aim for $5,000,000.

June 10, 2014: Campaign introduces add-ons: allowing fans to buy more merchandise. Means that existing backers can increase their pledge and help get towards goal.

June 12-13, 2014: Campaign adds new ‘Star Trek’ rewards. Both amount pledged and backer numbers spike.

June 19, 2014: DVD add-ons released, and the ‘add-on’ process was pushed to allow people to buy more merchandise with a moderate spike in support.

June 26, 2014: Campaign passes $4,000,000 pledged. Announces new “hang at a fan convention” rewards. A noticeable spike.

June 27, 2014: Seth MacFarlane announces he will match the next $1,000,000 of pledges, resulting in a massive spike of support.

June 28, 2014: The other 4 projects in Kickstarter’s “Top 5” agree to help with cross-promotion, and offer individual rewards. Pebble Watch and Pono offer limited edition watches; Ouya jumps on board as a supplier and offers a limited edition reward; Veronica Mars cast agree to a public reading.

July 1, 2014: With 48 hours to go, the project surpasses Veronica Mars for largest crowd on Kickstarter.

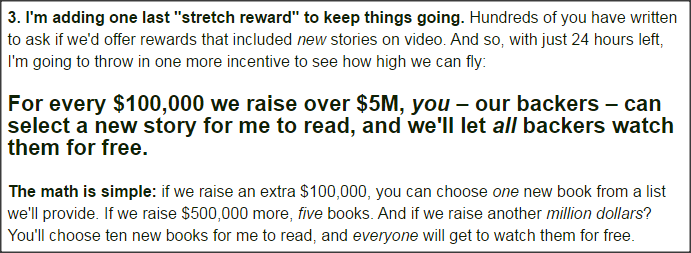

July 2, 2014: Creeping up on their $5,000,000 stretch goal, one more stretch goal is released in the final 24 hours.

July 3, 2014: Campaign closes with $5,408,916 raised from 105,857 backers, plus $1,000,000 in matching from Seth MacFarlane.

What they got right

Reading Rainbow waited until they funded before releasing stretch goals – in fact they were at 200% before they talked about them.

They also raised the money in two ways:

- Encouraging new backers with new rewards, asking backers to share the project, and continuing PR.

- Encouraging larger pledges through new rewards and ‘add ons’.

The partnerships with other projects opened them up to new audiences who were already familiar with crowdfunding. Both Veronica Mars and Pebble Watch sent out backer updates.

And the final stretch goal was an acknowledgement of the momentum the campaign picked up in the final 4 days. It gave people a reason to keep going past $5 million.

What are the key lessons?

- Stretch goals should galvanise a crowd and make use of existing momentum.

- A good stretch goal makes your project better, without adding a whole lot of work.

- Have a few stretch goals in mind when you launch, but don’t publicise them until you have funded. Ideally you should be considerably over funded before thinking too hard about stretch goals.

- Remember you need to make it better for your existing backers, and incentivise for new people to join in too.